So, it’s been a while since we’ve written anything here. Quite a while, in fact. That’s because we’ve been busy over here: Christchurch Archaeology Project. This is a project that’s grown out of all the post-earthquake archaeological work in Ōtautahi Christchurch, as we seek to preserve, share and use all that data. Come on over and check out what we’re up to – we think it’s pretty cool! Oh, and there’s a blog there too, in case you were missing that.

The importance of context

While walking through the city a month or so ago, I was stopped in my tracks by an unassuming sign: Shands Lane. For me, this small sign captured much of what is difficult about protecting, preserving and remembering our past in an urban environment. The sign refers to an early 1860s building popularly known as Shand’s, a name bestowed on it in the 1970s. The building was not named for an early occupant of the building, as might be assumed, but for the John Shand who owned the land when the building was constructed. John Shand was a farmer, racehorse breeder and hotelier. He neither built nor occupied the building and no other Shand is known to have done so (Christchurch City Council 1982). The building was moved to Manchester Street in 2015 (where it still stands), largely to make way for the access way now called Shands Lane.

Much was made of the need to incorporate lanes into central Christchurch following the earthquakes, with commentators frequently observing how laneways had revitalised central Melbourne. This discussion ignored that Christchurch had lanes prior to the earthquakes. Poplar Lane is one that people might remember, because it was used in the same way that the Melbourne lanes are, for shops and bars. Woolsack Lane (now the entrance to the Les Mills car park) is likely to be less familiar. These lanes are now gone, and there is no trace of them on current maps of the city. In 2017, the then head of Ōtākaro described the new lanes as “very much about giving character to Christchurch” (Small 2017), as though the city did not already have a character of its own, derived from multiple factors. More relevant might have been the point made by a local architect, that our city blocks are large, and constructing lanes through them provided more street-front commercial space within the city, particularly for retail outlets, cafes and bars (Dalman 2017). Shands Lane does indeed provide access to such premises, including a bar in a faux heritage-style building, which seemed to me to be the ultimate irony.

In general, heritage practitioners regard moving a building to preserve it as a last resort: preservation in situ is much preferred. This is because part of the meaning a heritage site – or artefact – derives from its context, from its connections with the place and environment in which it was originally constructed and used, even when that landscape has changed dramatically. The Shand’s building was built on Hereford Street, a location that placed it near the commercial heart of the new city. The solicitor who constructed the building no doubt chose the location for this very reason.

There is nothing at Shands Lane today to indicate why the lane is named as such, and so the name, too, is devoid of any context, like the building the name derived from. It is simply one name among many and I imagine few stop to think about it. It is a lane named for an 1860s building that was only named as such in the 1970s, that had to be moved so that the lane itself could be built, with no interpretation to recognise that a nod to the past is being made. Some form of interpretation would make the remembrance of this name more meaningful, and helped to demonstrate some of the layers of history within the city.

For me, Shands Lane serves as a reminder about how history is constructed and reconstructed as time passes, of how knowledge is lost and of how there can be an element of myth-making to the presentation of the past. This is only one very small – and quite harmless – example of this process. As has been discussed much in the media recently, incredible injustices and harms can result through misrepresentations of the past. History is no one fact, it is a story about the past and, like all stories, it is constructed by people to serve their own ends.

For more about the Shand’s building, see the Christchurch City Libraries website: https://my.christchurchcitylibraries.com/shands-emporium/

Katharine

References

Christchurch City Council, 1982. The Architectural Heritage of Christchurch No. 2: Shand’s Emporium. Town Planning Division, Christchurch City Council.

Dalaman, R., 2017. “Christchurch’s New Laneways.” Style, 1 June 2017. [online] Available at: https://issuu.com/the.star/docs/117152sm/34

Small, J., 2017. “Christchurch’s south frame laneways will become an ‘inner city oasis’ – Wagner.” Press, 26 June 2017.

Of universities and architecture

So, way back in the mists of time (i.e. about a couple of months ago…), we promised you a blog about the house built on this site after the existing house burnt down, tragically killing the son of the occupants. And, at last, here it is! Because even the most attentive reader is likely to have forgotten what that earlier post was about, here’s a quick reminder: Jessie wrote about the material culture used by Florence and Howard Strong in the late 19th century, Howard being the Head Librarian at the Christchurch library at the time.

Jessie’s post finished by talking about how the artefacts from the librarian’s house represented a more personal element of the history of Christchurch’s public library, an aspect of library history that is perhaps not often documented. In talking about the ‘new’ house today, I am returning to a more institutional aspect of the library’s history, but one where the institutional and the personal intersected. The house built for the Strongs following the 1894 fire was built by Canterbury College (now the University of Canterbury) for the librarian and his family to live in. This, then, was a case of an institution making decisions that would affect the lives of those who lived in the house. It is too strong in this case to say that such decisions would have controlled the lives of the occupants – this was a fairly standard house – but that was certainly true when some institutions built residences: think of asylums, orphanages, gaols and even hospitals. The librarian’s house is more akin to a manse, a caretaker’s house or a sexton’s cottage. It is a very different thing to live in a house that someone else has built for you, as opposed to one you have built yourself. In this situation, you really have no choice at all. While it’s possible that the Strongs were consulted about their new house, it seems likely that such consultation would have related only to the interior: the library was in the heart of the city with the librarian’s house right next to it. This was a prominent location and Canterbury College was an organisation that was very conscious of its image, and of the how architecture contributed to that image.

At the heart of Canterbury College’s was the university itself, now The Arts Centre of Christchurch Te Matatiki Toi Ora, and undeniably an architectural taonga. (Side note: I was intrigued to learn during the course of researching this blog that the College actually built the first library building (in 1874) before it built the first of the stone university buildings (in 1877)). The university chose to build in the Gothic style (as did the two high schools – Christchurch Girls’ and Christchurch Boys’ – that also built on the university site). A number of Christchurch’s significant early buildings were built in this style (or, more accurately, the Gothic Revival style – quite frankly, architectural ‘styles’ are a nightmare for someone who isn’t an expert). These included the Canterbury Provincial Council Chambers (1857), the Canterbury Museum (1870), Christ’s College (1863) and the Christ Church Cathedral (1864).[1] It is no coincidence that the university chose to build in the same style, which was synonymous with the ideals of the Canterbury Association (responsible for founding the settlement of Canterbury in 1850, and disbanded in 1852).

The Canterbury Association was formed at a time when some of the upper echelons of English society were becoming increasingly convinced that industrialisation had ruined England, not so much because of the societal or environmental costs that we might first think of today, but because it had destroyed England’s rural and feudal society and the Christian values that were part of that. A number of those who were instrumental in the association had connections with organisations that espoused these elitist views (such as the Tractarian movement, the Young England movement and the Ecclesiological Society) and they became one of the underlying tenets of the association. There was an architectural component to this: that the Church of England needed not just to return to the values of the pre-industrial church, but that its architecture also needed to return to the Gothic style. There was a strong nationalist component to this, which held that Gothic architecture was a true English style and therefore the only appropriate style for the Church of England to build in (Lochhead 1999: 46-50). As such, Gothic Revival was the preferred architectural style of the Canterbury Association. It intrigues me that most of the best-known buildings built in that style in Christchurch were built after the association was no longer, particularly given that many of the key values of the association were undermined even before their first settler had arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand. The ideal persisted for some, even if the reality was very different.

By the time the college embarked on building the university, the association was long since defunct and it is arguable that the Gothic Revival style in Christchurch was by now more about power (the Provincial Council buildings, although the provincial council was disestablished in 1876), religion (the cathedral) and education (the museum and Christ’s College). Each of these buildings were strongly associated with the elite, and thus Canterbury College positioned itself as an institution of and for the elite. The style and manner in which it was built also consciously echoed the university buildings of Cambridge and Oxford (Lovell-Smith 2001).

The library complex was located only a couple of blocks from the university, on the site of Puāri Pā Urupā (Tikao n.d.: 5). Puāri was a kāinga nohoanga (settlement) and kāinga mahinga kai (food-gathering place), located to the north of the urupā, on the banks of the Ōtākaro (Avon River). It was used for some 700 years, from the time of Waitaha up until the Kemp Purchase (1848; Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu 2020). In 1868, Ngāi Tūāhuriri tried to claim the site (and that of Ōtautahi) through the Native Land Court, but were not successful (Tau 2016).

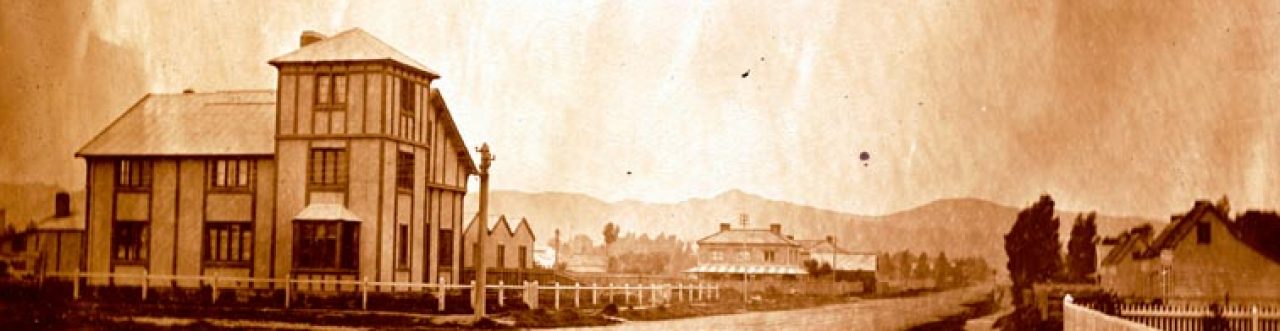

The library was built in a very different style from the university. The first of the buildings, constructed in 1874, was Venetian Gothic and designed by W. B. Armson, who was particularly known for this style. It was a single storey brick building with limestone details and a slate roof. In stark contrast to the Gothic Revival style, Venetian Gothic had strong associations with commercial buildings and commercial prosperity and was a style that looked more to Italy than the English Gothic (Ussher 1983: 13). The commercial connotations make it a curious choice for a library. The second library building, built in 1893, could not be called Venetian Gothic, but certainly echoed elements of the first building: it was brick, with limestone detailing (including limestone window surrounds), pointed window arches and brick dentils under the eaves. The following year, the college rebuilt the librarian’s house.

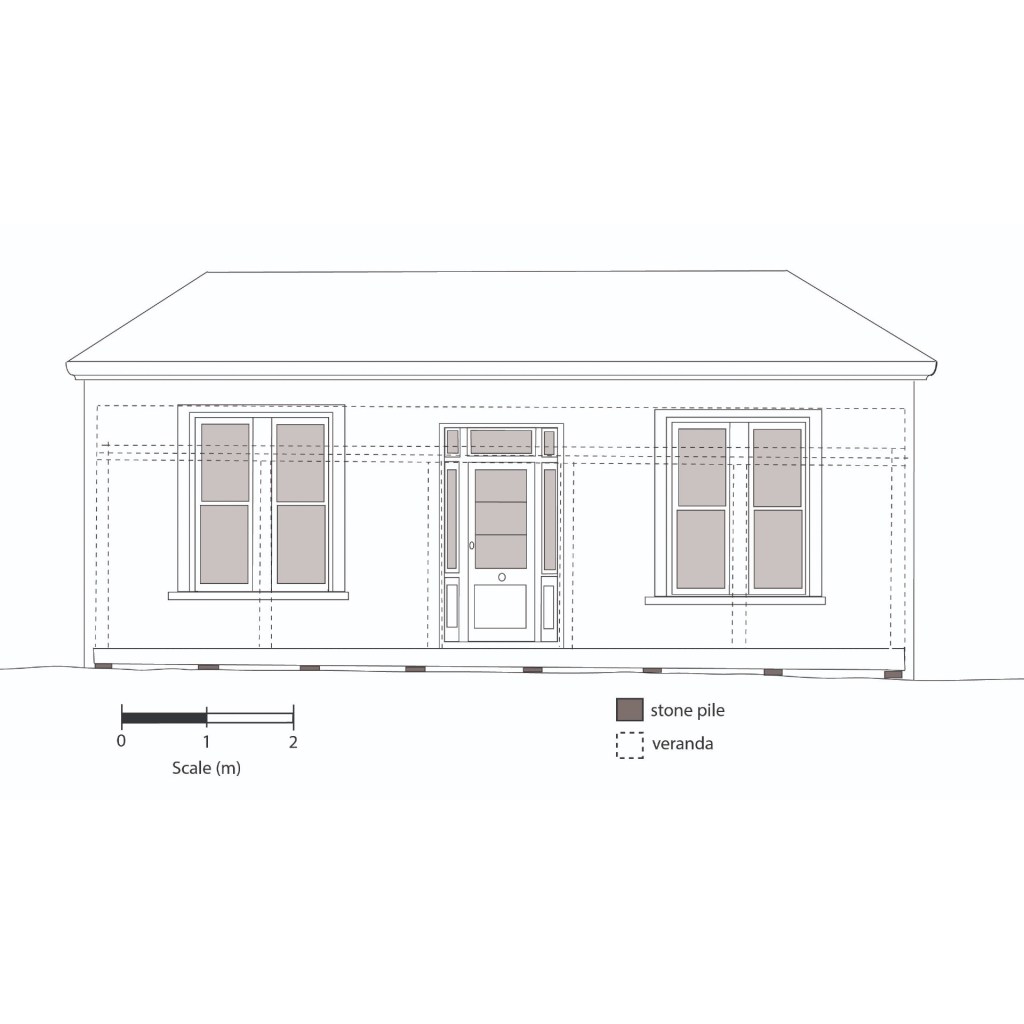

At this point, they turned to Collins and Harman, the architectural firm that Armson had founded and who had designed the 1893 addition. What brief the college gave the architects is not known, but the plans are now held at the Macmillan Brown Library. These indicate that the university were uncertain about exactly what they wanted, for two different drawings were prepared for the street-facing elevation. Both options were two-storeyed, with a veranda and the same number and arrangement of windows. The front doors were identical, as were the veranda posts. The main difference lay in the materials used, and the concomitant effect this had on the decorative details: one design was to be built in wood, the other in the brick, with limestone detailing and polychromatic brickwork in the gable apex. The wooden house was to have pierced bargeboards (in wood) and stickwork in the gable apex. The window surrounds on the two designs were quite similar, both featuring label moulds (an important component of Gothic architecture) above the windows in the bay, although these were to be executed in wood on the wooden version and in limestone on the brick version. The wooden version also appeared to have some slightly Gothic detailing at the top of the windows in the bay on the ground floor – not quite the quatrefoils of the 1893 building, but something akin to that. The wooden house was to have eaves brackets, while the brick one was to have brick dentils below the decorative brickwork in the gable. Stylistically, the wooden house was probably influenced most by Arts and Crafts ideas or the American stickwork style, while the brick version was perhaps more Queen Anne in style.

Unsurprisingly, the university chose the brick option, which was far more in keeping with the rest of the growing library complex (there were two further additions to the library, both of which were also built in brick with limestone detailing, although the Venetian Gothic influences were increasingly watered down).

I cannot help but think that the choice to build in brick must have been some comfort to Florence and Howard Strong, who had lost their son, home and contents to the fire that had destroyed the wooden librarian’s house. What is surprising to me, given the university’s clear sense of image (or ‘brand’, if you will), is that they even considered a wooden house, which would have been at odds with the other buildings. While the materials of the house matched those of the library, there was little that connected the two stylistically, and no real consideration appears to have been given to including Venetian Gothic elements in the house. Perhaps it was the case that, while building a library in the Venetian Gothic style was one thing, building a house in it was a step too far. Or perhaps it was a desire to visually distinguish between the house and the library that led to this decision. This could also explain why the university contemplated a timber design. In the end, though, they must have decided that they wanted the house to appear to be part of the complex at first glance, but to be different, unlike the case with truly institutional accommodation, such as the aforementioned asylums, etc.

Katharine

References

Lochhead, Ian, 1999. A Dream of Spires: Benjamin Mountfort and the Gothic Revival. Canterbury University Press, Christchurch.

Lovell-Smith, Melanie, 2001. ‘Arts Centre of Christchurch’ [online]. Available at https://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/7301 [Accessed 15 Decemeber 2020].

Tau, Te Marie, 2016. ‘The values and history of the Ōtākaro and North and East Frames’ [online]. Available at https://matapopore.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/GrandNarratives_InternalPages-Copy-small.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2020].

Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, 2020.’ Kā Huru Manu’ [online]. Available at https://www.kahurumanu.co.nz/atlas [Accessed 15 December 2020].

Tikao, Debbie, n.d. ‘The Public Realm of Central Christchurch Narrative’ [online]. Available at https://www.otakaroltd.co.nz/assets/Uploads/ThePublicRealm.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2020].

Ussher, Robyn, 1983. ‘Armson in Christchurch’. In W. B. Armson: A Colonial Architect Rediscovered. Robert McDougall Art Gallery, Christchurch. Pp. 13-16.

[1] These dates refer to when construction of the first stone part of each of these buildings/complexes. Some, such as the cathedral, took many years to complete, while others were part of large complexes that kept on growing.

The children of Cora Villa

It’s an oft repeated phrase that children are frequently difficult to see in the historical record. Other than records of births, deaths and unfortunate accidents, children – that is, the lives of individual children, named and known – are far more scarcely represented than their grown-up counterparts. The antics of children, seen through the lens of an adult perspective, unsurprisingly, are there in the newspapers, in diaries, letters and books, but these stories are at best generalisations and at worst exaggerations.

This is not to say that the lives of children are completely unknown to nineteenth century New Zealand history – I’ve got a great book about the history of child’s play in New Zealand (Sutton Smith 1981), for example – but that, unlike so many of the people we encounter in the archaeological record, who have names and faces and stories, children usually remain – at best – a name and a date of birth. Similar to the treatment of women in some parts of the historical record, they are often considered an extension of the adults (usually men) to whose stories they belong until they are old enough to be known for themselves.

Cora Villa, the subject of the exhibition that’s just finished at South Library, is therefore all the more fascinating for the material and documentary evidence it provides for the lives of the children who were born or sheltered within its walls and who, I like to think (perhaps romanticising a little) ran through its rooms and played in its garden. At least five children were born at the house between 1878 and 1900. At least another three lived there in the early 1900s and it’s entirely possible that more children came and went with their parents in the intervening years. Some of their names and stories remain known, and some do not. Charles and Agnes Marshall welcomed three children during their time at the house, between 1885 and 1893: James, Agnes and Kuini Mei. James and Agnes are not particularly easy to trace (too many people of the same name!), but Kuini Mei passed her Junior Civil Service exams in 1907 and went on to become an accountant, passing University of New Zealand exams in “auditing and trustees, bankruptcy, and companies” in 1913. All three, the children of Scottish immigrants, also make frequent appearances in Caledonian Society events along with their parents (there is nothing at all embarrassing in these accounts, but it still makes me exceedingly grateful that no-one will ever be able to read similar records of things I attended as a kid…).

It is likely that at least some of the many children’s artefacts found underneath Cora Villa belonged to the Marshall children. Several children’s cups (or cans, as they are known) from the assemblage were likely made by the Brownhills Pottery Company between 1872 and 1896 (Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab 2012; Riley 1991). A couple of the designs were first registered in the 1883 and 1885 and it seems quite likely that they could have belonged to James (b. 1885), Agnes (b. 1887) and Kuini (b. 1891) before they were abandoned under the house.

Nineteenth century children’s crockery often featured designs from well-known stories, morals or publications on their surfaces, sometimes accompanied by blocky, coloured alphabet motifs (entirely predictably, these are known to collectors as ABC plates). The scenes depicted on cups and plates could sometimes be simple and colourful, showcasing typical aspects of childhood, or lean towards more educational and morally specific depictions at the ‘moralising china’ end of the spectrum. The array of children’s cups from Cora Villa include both, from a colourful ABC cup depicting a family boating at the beach (including what looks like a baby with really long arms buried in a sand dune?) to a cup decorated with a maxim from Benjamin Franklin’s alter ego Poor Richard. There’s a cup with the title “DUBLIN”, beneath which the River Liffey trudges past the Dublin Custom House and the old Butt Bridge (tried hard not to laugh at this, failed, I am terrible), and my personal favourite, a cup where the title “LETTER” does not at all adequately describe the scene of two people who have apparently decided to post letters to each other through the medium of a tree, rather than the postal service.

The Benjamin Franklin/Poor Richard cup is particularly interesting. Poor Richard’s Almanack was written and published by Benjamin Franklin in the late eighteenth century and became well-known for the wealth of proverbs and axioms it provided, especially to those in the nineteenth century (Riley 1991). This particular cup, which features several men (one of whom, shockingly, does not appear to be wearing any pants – poor shading, that) hard at work with spades and pick-axes, would have originally read: “Handle your tools without mittens, remember the cat in gloves catches no mice; Constant dropping wears away stones and little strokes fell great oaks” under the title “THE WAY TO WEALTH OR DR FRANKLIN’S POOR RICHARD ILLUSTRATED, BEING LESSONS FOR YOUTH ON INDUSTRY, TEMPERANCE, FRUGALITY”. The patience and perseverance moral of the second adage seems fairly obvious, especially with the image of men (pantsless or not) chipping away at the earth, but there’s a part of me that really wishes the illustrator had instead gone with an image of a cat chasing mice while wearing gloves.

Moralising china says something about Victorian society, about manufacturing and marketing choices, but also about the values of parents – particularly because there’s an assumption that people will police their consumer choices more when their children are involved. I’d love to draw a connection between the Scottish heritage of the Marshall family, the stereotype of the staunchly moral Scots family in New Zealand, and the hardworking, persevering values of this cup, but I think it’s a bit of a stretch – it’s far more likely that the fairly standard values of hard-work and patience appealed to them, as I’m sure they did to many other nineteenth century families.

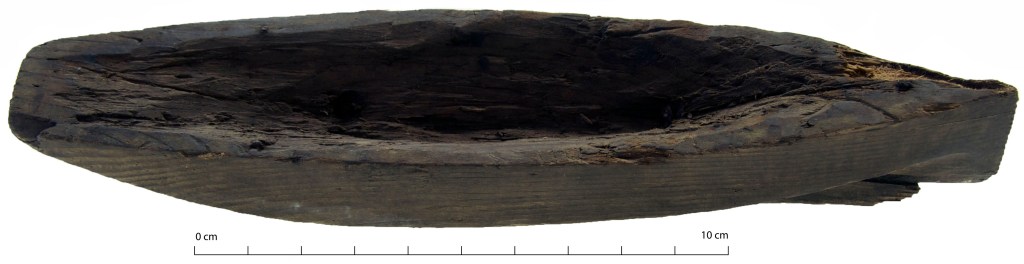

Other children’s artefacts from the underfloor assemblage shift us away from the educational and practical aspects of children’s lives, to play. In particular, a hand-carved toy boat was found in one corner of the house and it is not hard to picture the tiny humans of the house – be they the Marshall children, or the children of later tenants (the Bradbury family, the Goodwill family, the Elstob family) – playing with it in the shallows of the nearby Avon River. It may have been used in races, endless hours of fun created from the natural current of the river and a hollowed-out piece of wood, before it was outgrown or lost under the house.

Unfortunately, not all the stories of the children of Cora Villa were good ones. The children of the Elstob family lost their mother there in tragic circumstances in 1910, and there is something inherently sad by association in the early 20th century children’s artefacts from the assemblage that may have belonged to them – a cup decorated with the faded print of children skipping rope, the fragment of a possible christening cup. What did these objects mean, to those children, at that time?

While I do not think I would have liked to be a Victorian child, especially a Victorian girl-child (much too contrary, full of opinions and FAR too fond of climbing trees!), these toys and plates do feel familiar in a way that I suspect children’s toys always will, no matter where or when they come from. I go on a lot (here and everywhere, sorry everyone who knows me) about artefacts as things of meaning, objects that mean more than their physical manifestation and I think this is true of children’s artefacts more obviously than most. Toys and cups and favourite things mean so much when you’re a kid – they’re the difference between a crying child and a smiling one, a child who will sleep and one that won’t. They bring comfort, joy, safety, familiarity and I don’t know what else – I imagine most of us can remember an object we loved as children, that meant so much more than it should have. In turn, as adults, those artefacts carry a nostalgia with them, a physical reminder of our own childhoods, or of the notion of ‘childhood’ in general, sentiment that makes them more than just an unusually decorated small drinking vessel or a miniature version of a boat. They’re evocative, and these particular children’s artefacts evoke for me the lives of the children who lived in Cora Villa over a century ago. They breathe life into the names in the newspapers, children made somehow more real through the old toys I hold in my hands.

Jessie

References

Barshter, N., and Chappell, B., n.d. Brownhills Pottery Alphabet (ABC) ware Birds. [online]. Available at: http://www.oldchinaservice.com/transferware/brownaesthetic/aaestheticindex.html [Accessed November 2014].

Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab, 2012. Alphabet Wares. [online] Available at:

http://www.jefpat.org/diagnostic. [Accessed November 2014].

Mitchell, P., Geary Nichol, R. and Jackson, G., 2015. 396 Oxford Terrace, Christchurch. Report on Archaeological Monitoring. Unpublished report for CERA.

Riley, N ., 1991. Gifts for Good Children: The history of children’s china 1790-1890. Richard Dennis, England.

Sutton Smith, B., 1981. A History of Children’s Play: The New Zealand Playground, 1840-1950. University of Pennsylvania Press, Pennsylvania.

Home and contents: life in the Avon loop

Joseph Francis was the only member of his family who didn’t enter the woollen mills in Wiltshire. Instead, he trained as a solicitor’s clerk, a position that would have ben a step up the social scale. At the age of just 20, he married Harriet Hall, and the pair immigrated to Christchurch shortly thereafter, no doubt hoping to improve their fortunes (Ancestry 2020). In 1878, about two years after they’d arrived, Joseph commissioned local architect J. C. Maddison (who would go on to become quite prominent) to design him a house for land he’d purchased on Oxford Terrace in the Avon loop (Lyttelton Times 1/10/1878: 4, LINZ 1879). At this time, Joseph was working as a waiter in a hotel owned by one Joseph Oram Sheppard (Globe 17/2/1879: 2). Having an architect design your house still isn’t exactly the norm, but it was even less common in 19th century Christchurch, when houses were probably largely designed by builders, or selected from a pattern book. And how a waiter came to have sufficient funds to commission an architect is still not clear to me. Given his and his family’s occupations, it seems unlikely that Joseph had brought much money with him from England, and most of the funding the architect, the house and the land is likely to have come from the mortgage he took out against the property (the aforementioned Sheppard was the mortgagee).

The Avon loop (the area between the Avon River, Barbadoes Street and Kilmore Street) was just starting to develop when Joseph bought his land there. By 1877, there were a number of houses in the southern part of the loop, and around what would become Hurley Street, but few elsewhere. The roads that were to be formed in the area had been surveyed in 1877 but were not built for another few years. These roads were not part of the original survey of Christchurch and, while they conformed to the overall grid plan, several were dead-end streets, and thus the neighbourhood was not as interconnected as or with other parts of the city (Farrell 2015: 151-156). Joseph and Harriet’s house was built on a section on Oxford Terrace, and faced north across the river. This would have given it a pleasing aspect, and one somewhat different to the houses within the heart of the loop. In other words, this was perhaps a slightly better location than, say, Hurley or Willow streets. An aerial photograph of the loop from 1959, when many of the 19th century houses still stood, indicates that the houses on Oxford Terrace and Bangor Street were typically villas, while those on Hurley and Willow streets were more likely to be cottages. By the mid-1880s, the loop was largely completely occupied, and most of those occupants were working class.

For all that he commissioned an architect to design his house, it was in fact a very ordinary house for the times. It was a square villa, with a veranda, built largely from kauri. There were some quite plain brackets on the veranda, and the house had double sash windows on the front, as well as both fan and sidelights on either side of the front door. These were all signs that the house was a cut above the basic cottage. Inside, there were seven rooms: a parlour, two bedrooms, a kitchen, a scullery, a pantry and the hall. The house was 81 m2, making it considerably smaller than 105.4 m2 (the average size of the 101 19th century houses in the sample I’m looking at for my PhD), but larger than the average Avon loop house. The house was lined throughout with lath and plaster, except in the kitchen, where there was wainscoting. Unusually, even the pantry was lined with lath and plaster (match-lining was more common). It had traditional moulded skirting boards, and these were higher in two of the three public rooms (the hall and the parlour, but not the master bedroom) than in the rest of the house. Unfortunately, the fireplaces had been removed long before the archaeological recording.

It’s not at all clear whether Joseph, Harriet and their young family ever lived in the house. The architect called for tenders for its construction in October 1878, and Joseph was advertising it for lease in November the following year (Lyttelton Times 1/10/1878: 4, 9/12/1879: 1). In these advertisements, he gave his address as the Junction Hotel in Rangiora. Of note is that, when advertised for lease, the house was called Cora Villa, a name that continued to be used until at least 1916 (Star (Christchurch): 1/4/1916: 10). It seems that Joseph and Harriet named the house for their infant daughter Cora, who died not long after her birth in 1878 (Ancestry 2020).

Joseph continued in his career as hotelkeeper, moving from the Junction to the South Rakaia to the Rolleston hotel in fairly quick succession (Press 15/5/1880: 5, Lyttelton Times 8/10/1880: 1). Advertisements letting the house appear from time to time throughout this period. In 1881, Sheppard foreclosed on the mortgage (LINZ 1879). The following year, Sheppard also forced Joseph to sell the Rolleston Hotel lease, to recover debts that Joseph owed him. By this time, Joseph had mortgages worth more than £1400 (he owned property in Waimate, Christchurch and Rolleston), as well as debts to suppliers (Star (Christchurch): 30/6/1882: 3). By July 1882, he was unemployed (Lyttelton Times 20/7/1882: 7).

It’s not entirely clear what Joseph did next. Harriet died in 1887, having borne Joseph as many as seven children (the records are a little hazy), the oldest of whom was 11. As was often the case in a situation like this (widowed man, a number of young children), Joseph quickly remarried, to one Nellie Britt, who would have two children with Joseph (Ancestry 2020). The following year, the couple were living in Timaru, where Joseph was working at the Club Hotel, as a waiter (NZER (Timaru) 1893: 22). Joseph died in Timaru in 1894, aged 39 (Ancestry 2020, Timaru Herald 3/7/1894: 2). And Nellie? Well, it’s not clear – Ancestry records her as dying in 1895, but provides no reference for this information, and there’s no record of her death in Births, Deaths and Marriages (Ancestry 2020).

Sheppard retained ownership of the house for a couple of years, possibly briefly renting it back to Joseph and Harriet, before selling to Charles Fox in 1883. Charles was an accountant, who owned the house for about a year (and lived there) before selling to Charles Marshall (LINZ 1883). This Charles was a newly married law clerk, and he and his wife Agnes would have three children at the house, before also selling up and moving on in 1891 (LINZ 1883, Star (Christchurch): 4/10/1884: 2, 29/12/1887:2, 20/5/1891: 2, Press 27/6/1885: 2). After this, the house was owned by one Therese Schuster (later Therese Wisker) into the 20th century. Therese rented the house out to a succession of occupants. Even after she sold it, it remained a rental property for the rest of the century (LINZ 1883).

Cora Villa is the subject of an exhibition that we’ve curated as part of the Christchurch Heritage Festival , being held at the South Library . This blog explores just part of the story of the house and those who lived there. Over the course of the next two weeks, we’ll be featuring more of these stories – and the artefacts that go with them – on our Facebook and Instagram pages. Enjoy!

Katharine

References

Ancestry, 2000. ‘Joseph William Francis’ [online] Available at: https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/13599389/person/12981309397/facts [accessed 21 October 2020].

Farrell, Fiona, 2015. The Villa at the Edge of the Empire: One Hundred Ways to Read a City. Vintage, Auckland.

Globe. Available at https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

LINZ, 1879. Certificate of title 38/187, Canterbury. Landonline, Land Information New Zealand.

LINZ, 1883. Certificate of title 92/203, Canterbury. Landonline, Land Information New Zealand.

Lyttelton Times. Available at https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

NZER (New Zealand Electoral Rolls) (Timaru), 1893. Available at: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1836/

Press. Available at https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

Star (Christchurch). Available at https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

Strouts, Frederick, 1877. Christchurch, Canterbury, 1877. Ward & Reeves, Christchurch.

The librarian’s house

Libraries are a gift. There is something magical about their existence; about the otherwise ordinary rooms and halls transformed by the books that amass on shelves and displays; a congregation of knowledge in a single space that somehow feels bigger than its physical reality. They’re places that represent more than the sum of their parts, institutions that give us the ability to travel through time and space, across universes and into worlds we’ve only dreamed of (as always, the inimitable Terry Pratchett captured this well in his concept of L-space).

Libraries were also valued by early European colonists, although perhaps not quite so whimsically. Books were relatively scarce in the colony: the expense and distance between New Zealand and European publishers made it difficult to regularly source new reading material (and, very likely, further restricted the privilege of reading to those wealthy enough to spend their time and money on books). Access to reading material was presented in the newspapers of the time as a necessity, in line with the aspirations of many settlers – particularly those involved in the civic shaping of their new society – to make Christchurch (and New Zealand) a center of education and improvement. Others expressed sentiments familiar to people in the present day (and, I suspect, throughout time): boredom and a wee bit of FOMO, hearing of the new books published in Britain and Europe, yet having to wait for months and months to read them.

The history of the public library in Christchurch is actually a little bit complicated. The first public library established in the city had its foundations in the Christchurch Mechanics’ Institute, founded in 1859, but didn’t really exist as a public library in a way we might recognise it today until the mid-1870s, when it came under the purview of the then Canterbury College (the Christchurch City Council didn’t take it on until the 1940s – I did not know this!; Christchurch City Libraries 2020).

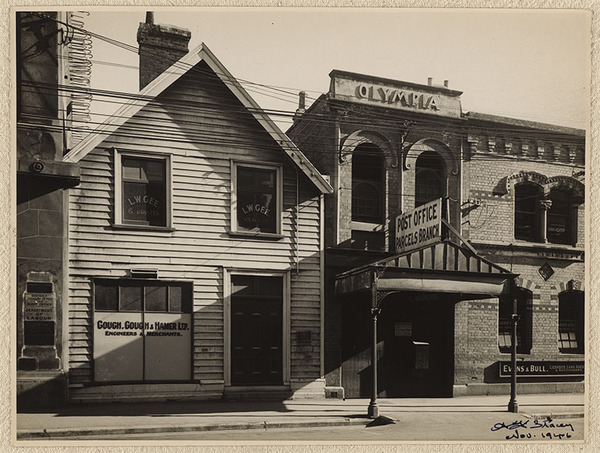

For those unfamiliar with them, mechanic’s institutes were a relatively common facet of life in the nineteenth century, founded with the intention of educating and improving the lives of their members, who were usually tradespeople, craftspeople and skilled workers (Christchurch City Libraries 2020). As with organisations like the Oddfellows, Working Men’s Associations etc., mechanic’s institutes were part of movements to improve the lot of the working classes – in this case, through lectures, public events, classes and entertainments and, most importantly, the provision of a library. This would have been contrary to the aims of the Canterbury Association, and many of the prominent early colonists, some of whom were decidedly of the opinion that education and knowledge should NOT be available for all, especially those pesky working classes (John Robert Godley had a lot to say on this and it was not good; McAloon 2000: 162). However, despite an early setback (the first attempt was not successful), the Christchurch Mechanic’s Institute was established in 1859 and the library it provided became “the most important element of the Institute’s work” (Christchurch City Libraries 2020). To that end, the Institute changed its name to The Literary Institute in 1863, when it moved from the Town Hall to a site on the corner of Cambridge Terrace and Hereford Street. By the mid-1870s, however, among financial and organizational difficulties, the library was handed over to the College and a William Armson-designed building erected next to the earlier 1863 structure on the site.

With libraries come librarians and, believe it or not, this is actually a blog about a librarian – specifically, the librarian who lived in the house next to the library on Cambridge Terrace. His name was Howard Strong and he was involved with the Christchurch Public Library from c. 1879 until his retirement in 1913, first as Sub-Librarian and then as Head Librarian from 1908 to 1913 (Christchurch City Libraries 2020). During his time with the library, he and his family lived on the premises, in a house right next door to the library building itself. There’s something to be said here about the proximity of living space to workspace, particularly in light of the evident difficulties that could be caused by living at a distance from work, as Kat mentioned in the last blog. It’s not something that we seem to concern ourselves with so much in the present day – at least not to the degree of living next door to our workplaces (if anything, there seems to be more of a desire now to separate places of work from places of living).

Howard was English, with a relatively interesting background, having been privately educated in England and Brussels and arriving in New Zealand at the age of 19, after three years at sea (as a sailor; he did not make the crossing to New Zealand by way of the world’s slowest moving raft; Press 24/09/1924: 11). He was very much an active participant in the colonial venture: he spent just over a decade of his life in New Zealand, prior to becoming librarian, fighting in the North Island on behalf of the colonial government and constabulary forces against local Māori. This included time as a volunteer under the command of George Whitmore during the pursuit of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Tūruki, the Ringatū prophet and warrior, and Tītokowaru, the Ngāti Ruanui leader, military strategist and prophet. If you’ve not heard much of Te Kooti and Tītokowaru before, theirs are truly fascinating stories: both of them were men of faith, warriors and leaders, famous for their defiance of the colonial government during the 1860s and 1870s (Te Ara 2020; O’Malley 2016). If you have time, you should absolutely read more about them (I may or may not have lost a couple of hours to reading about them over the course of writing this…).

In 1875, Howard married Florence Bach, moved to Christchurch four years later and, over the course of the next little while, the couple had eight children. As is typical, there’s not a lot of existing information on Florence: her father was from Birmingham and she mostly appears in public notices and newspapers through advertisements for servants and the occasional mention in association with the library or local events. The family appear to have lived in the house next to the library from the late 1870s until 1894, when tragedy struck. A fire broke out in the house and, although Mr and Mrs Strong and seven of their children escaped injury, their 9 year old son died in the fire, which also destroyed most of the house and its furnishings. A new house (which Kat will talk about on the next post) was constructed in place of the burned building and survived through the twentieth century until the earthquakes necessitated its demolition.

In 2012, archaeological work on the site of the librarian’s house found evidence of this fire through a burn layer beneath the foundations of the new house, very clearly associated with the events of April 1894. Mixed in with the layer was the detritus of the destroyed Strong household, through the broken and burned objects they owned at the time of the fire. The assemblage is unique in Christchurch, and unusual more generally, as we don’t often have such a clear and narrow date for the deposition of artefacts in the archaeological record. You’ll have seen that in my captions on other posts – artefacts that date to “the 1850s-1870s” or similarly vague periods of time. In this case, it’s not just that we know that the objects were disposed of in 1894, it’s that they would have been deposited as a result of the fire and so, they offer a sort of glimpse through time to the contents of the Strong household in April 1894 – or, at least, those contents that could not be salvaged after the fire (even an assemblage like this is curated by what people – the Strongs – valued enough to save or to leave; Beaudry 2005).

The assemblage contains much that is familiar and expected for a domestic household: fragments of stoneware storage jars, shards of pharmaceutical bottles, the spout from a teapot, the rim of a mixing bowl. A bottle of Bonnington’s Irish Moss may have been prescribed for colds and coughs in the household in the same way that we reach for Codral today, particularly in a household of eight children, at whom much of Bonnington’s advertising was targeted. A slate pencil may have been used and lost by one of those children in the course of their lessons (there’s little doubt that they would have been educated). Leather shoes worn by the family are evocative of the individuals who wore them.

Some of the vessels were more identifiable. For example, a “porcelain” (actually glass) seal for a preserving jar, perhaps used by Florence Strong or the help she advertised for in the kitchen of the house. An agateware doorknob shows a certain attention to detail and style when it comes to the furnishings and fittings of the house. A bowl marked with the stamp of ‘F. Primavesi and Sons’ provides a link not just to the consumer choices of the Strong household, but to the mechanisms of trade and mass production in the wider world of the 1880s-1890s: Primavesi and Sons were ceramic importers and dealers in Wales and England, a sort of ‘middleman’ between the pottery factories and the retailers who sold their wares (Tolson, Gerth and Cunningham Dobson 2008).

Most interestingly, perhaps, were a selection of vessels decorated with the appropriately literary “Tennyson” pattern, found in the burn layer. The effects of the fire were clear on the more than 250 fragments of this dinner set, in the melted glazes, scorched and soot-stained surfaces and the odd piece of shapeless glass fused to the pottery. That this was an assemblage of abandonment – that is, an assemblage created by circumstances that led people to abandon the goods they owned where they were left – is also reinforced by the number of different vessels from the dinner set represented in the archaeological record. Ordinarily the household waste that we create is the result of our actions and choices – the things that we break, the choice to throw out one vessel, but to repair another – and things like dinner sets may only be represented by one or two of the vessels from the set. In this case, however, it is very clear that the effects of the fire were indiscriminate (as also evident from the historic record), affecting nearly everything in the house. Consquently, the material footprint of that event provides a more comprehensive picture of the contents of an 1880s-1890s house than we might normally be able to see.

As a result, there’s also something to be said for the very clearly middle class status of the Strong household. The Tennyson dinner set is an example of aesthetic transferware, a style of ceramic decoration popular in the 1880s – it’s what has been termed a ‘high’ style of pottery, a style that changes with the fashions and trends of societies, falling in and out of vogue, in contrast to the more traditional styles – that is, the ones whose popularity remains relatively unchanged for decades – like the Willow pattern or the ever ubiquitous Asiatic Pheasants, neither of which are present in this assemblage (Majewski and Schiffer 2009). It suggests that Howard and Florence were able to keep up with the trends, so to speak, especially as one of the vessels had a mark dating its manufacture to 1888, meaning that Florence and Howard could only have owned it for six years at most. There are nods to more traditional, utilitarian styles – a Rouen plate, a banded mixing bowl – but not as many as might be expected. Instead, porcelain vessels and a matching chamber pot, wash basin and ewer set round out the ceramics from the fire (there does appear to be a certain preference for blue and green floral decoration, but whether this is representative of the time or the taste of Florence and Howard, I don’t know).

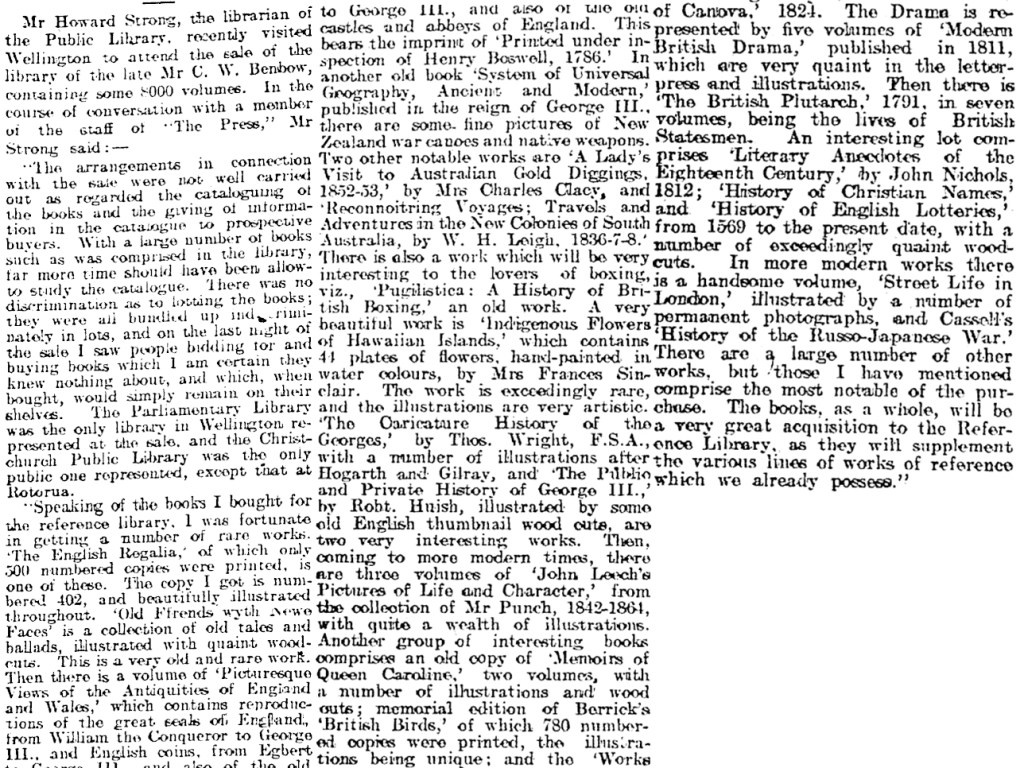

Alongside all of this, these artefacts carry the weight of their association with Howard and Florence Strong and the fire that proved so devastating to their family and to their home. They offer a glimpse into the domestic life of the librarian and his family, one that is not offered by the documentary record – we know far more about Howard Strong’s public role than we do about his household from the historical records of his life that remain. As an aside, my favourite of these is a 1908 account of a trip Howard made to Wellington to buy books from a sale – in it, he (like all good cataloguers) bemoans the disorder of the sale and discusses several of the treasured books he managed to acquire for the library. I had a look in the library catalogue and, what do you know, a handful of the books he was so happy to have bought in 1908 are still available at Tūranga in 2020, including Thomas Bewick’s A History of British Birds (1826) and Thomas Bankes’ A New Royal, Authentic and Complete System of Universal Geography, Ancient and Modern (1787-88).

We have very little – and are likely to always have very little – in the way of material or archaeological remains of the institution of the public library in Christchurch, with the exception of those artefacts, like Thomas Banke’s geography tome or Bewick’s bird manuscript, that have remained living objects in the library system through to the present day. The artefacts from the librarians’ house, on the other hand, offer a more personal perspective on the history of the library in Christchurch, a glimpse of the people who made the institution what it was, whose actions and choices and attention protected and encouraged the growth of an establishment that remains a magical and necessary part of the Christchurch community.

Jessie

References

Beaudry, M., 2015. ‘Households beyond the House: On the Archaeology and Materiality of Historical Households’. In Fogle, K. R., Nyman, J. A. & Beaudry, M. C. (Eds), Beyond the Walls: New Perspectives on the Archaeology of Historical Households. University Press of Florida, Florida.

Christchurch City Libraries, 2020. ‘A History of Christchurch City Libraries’ [online] Available at https://my.christchurchcitylibraries.com/brief-history-christchurch-city-libraries/ [Accessed July 2020].

Christchurch City Libraries, 2020. ‘The Mechanic’s Institute’ [online] Available at https://my.christchurchcitylibraries.com/the-mechanics-institute/ [Accessed July 2020].

Christchurch City Libraries, 2020. ‘ James Nash Howard Strong, 1840-1924’ [online] Available at https://christchurchcitylibraries.com/Heritage/People/S/StrongHoward/ [Accessed July 2020].

Majewski, T. & Schiffer, M., 2009. ‘Beyond Consumption: Towards an Archaeology of Consumerism’. In Majewski, T. & Gaimster, D. (Eds), International Handbook of Historical Archaeology. Springer.

McAloon, J., 2000. ‘Radical Christchurch’. In Cookson, J. and Dunstall, G. (Eds), Southern Capital Christchurch: Towards a city biography 1850-2000. University of Canterbury.

O’Malley, V., 2016. The Great War for New Zealand: Waikato 1800-2000. Bridget Williams Books, Wellington.

Te Ara, 2020. The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. [online] Available at https://teara.govt.nz/en [Accessed July 2020].

Tolson, H., Gerth, E. and Cunningham Dobson, N., 2008. ‘Ceramics from the “Blue China” Wreck’. In Ceramics in America 2008. [online] Available at http://www.chipstone.org/issue.php/9/Ceramics-in-America-2008 [Accessed July 2020].

Watson, K., 2012. 109 Cambridge Terrace, Christchurch: Report on Archaeological Monitoring. Unpublished report for CERA.

Watson, K., 2012. 107 Cambridge Terrace, Christchurch: Report on Archaeological Monitoring. Unpublished report for Christchurch City Council.

To build…

Concern about houses in New Zealand – whether the quality, quantity or location thereof – is nothing new. The development of so-called slums, in particular, alarmed nineteenth century migrants to Aotearoa New Zealand, many of whom had come here in the hope of escaping just such problems. By the same token, one of the appeals of nineteenth century Aotearoa to European migrants was the (relatively) unfettered access to land, particularly in urban areas, thanks to the Crown’s cheap acquisition (and in some cases confiscation) of that land from Māori. Not only was land readily available as a result, but there were also few controls on its use (Schrader 2005: 17). The tension here is obvious to us today, but state involvement in the property market (or any other aspect of life for that matter) was considered even less desirable then than it is now (Ferguson 1994: 5, Schrader 2005: 17). The election of the Liberal government in 1890, however, saw attitudes and approaches begin to change (Schrader 2005: 18-19).

Gael Ferguson and Ben Schrader have both documented the solution the Liberals implemented to try and deal with clusters of poor quality housing (Ferguson 1994: 45-45, Schrader 2005: 16-22), which I have summarised below. What I really want to explore, through two case studies, is the houses that were built in these settlements and the people who lived there, in order to move beyond the general to the particular and thus to better understand the individual experience of these hamlets, as they were known.

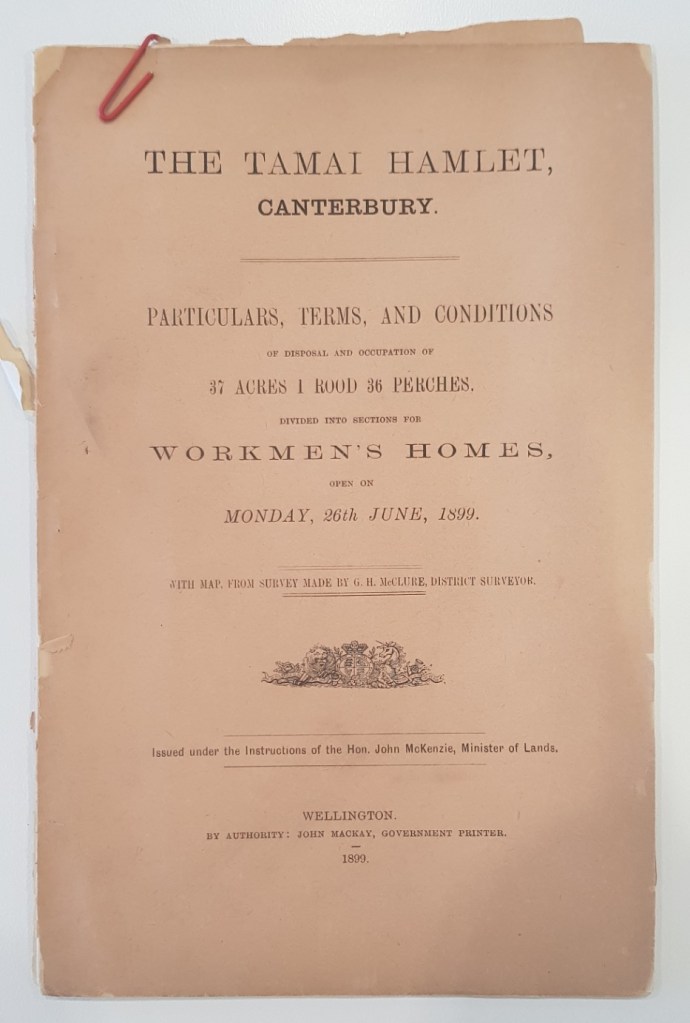

To solve the problem of slums, the Liberal government decided to establish working class settlements on the outskirts of Aotearoa New Zealand’s cities. These settlements were to be for working men and women, who would be able to lease a section (for 999 years), in return for meeting various requirements, including building a house within a year, fencing the land within two years and establishing a fruit and vegetable garden within three years. Successful applicants had to be able to prove that they had the means to build a house, or that they would be able to do so with a government loan. And they had to be “in all respects a deserving and suitable person” (Lands Department n.d.: 8-9). The sections were to be big enough for a productive garden that would support the occupant in times of little or no work (Schrader 2005: 20). It is perhaps no coincidence that the sections were sometimes referred to as “workmen’s home allotments” (Star 28/10/1896: 3).

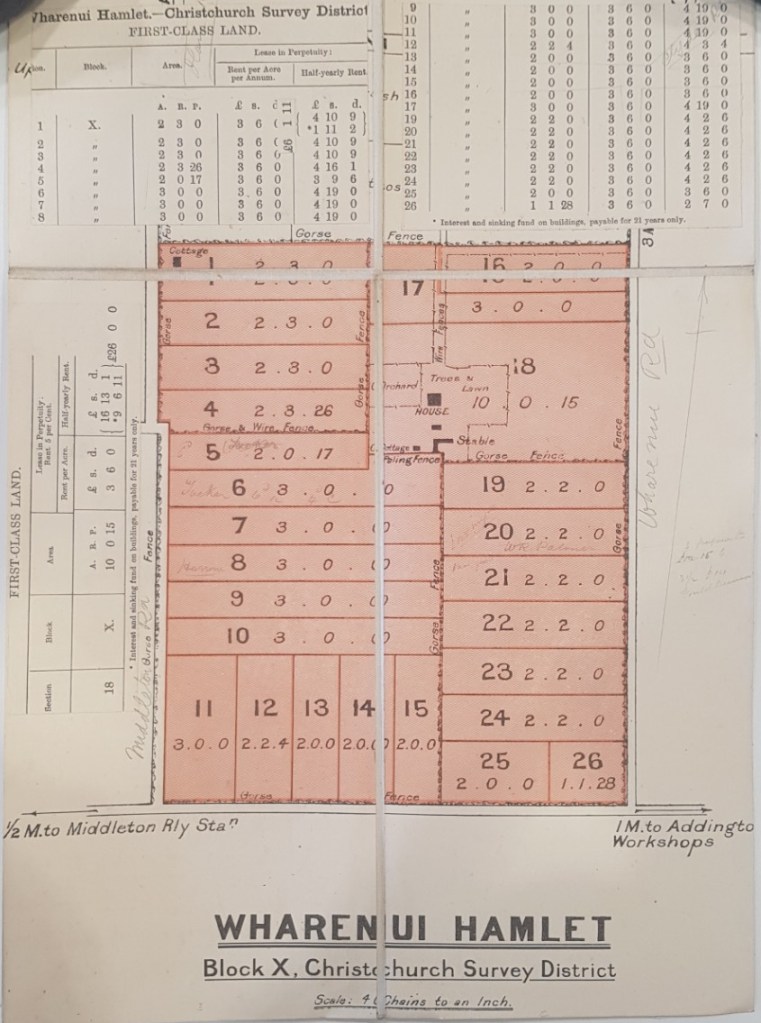

The first of these settlements – or hamlets, as they were to be known – was Wharenui, established in Christchurch (Ellesmere Guardian 3/4/1897: 2). The irony here is that the complaints about slums were generally about Auckland and Dunedin (Schrader 2005: 18) – in fact, I have found little reference to slums or rookeries, as they were often known, in Christchurch in nineteenth century newspapers. The land was opened for selection in March 1897 and, although there were a reasonable number of applicants, several applied for the same sections, with the result that only seven of the 26 sections were taken up (Press 9/3/1897: 1, Star 27/3/1897: 5). Those sections that were not leased to working men were offered on a weekly leasing arrangement to the New Zealand Loan and Mercantile Company and a Mr Chadwick, presumably for grazing (Star 9/4/1897: 2). As would be found throughout the country, the lack of public transport would limit the appeal of this scheme, along with the fact that sections could not be purchased or subdivided (Schrader 2005: 22). People wanted to live near their work, and the other supposed advantages of the scheme were not enough to outweigh the disadvantages.

One of the leaseholders at Wharenui was Hans Hansen, who took up his lease in 1898, not long after he’d arrived in the country from Ribe, Denmark, aged 36 (DIA 1899, LINZ 1898). Hansen leased Section 13, of 2 acres, for £6 12s a year (LINZ 1898). Within a year, Hansen had built a one-room dwelling, fenced the section, sunk an artesian well and was cultivating and gardening. The dwelling, however, did not meet the requirements of his lease, being worth less than £30, and he was granted an extension until 1 November 1901 to build an appropriate house, as well as a loan of £20 to do so (Lands Department 1898-1929). By 1904, when Hansen put the lease up for sale, he had built a two-room cottage on the land to replace the original dwelling (Press 3/2/1904: 10). Early in 1905, the lease was transferred to Alexander Grieve (LINZ 1898).

The second house Hansen built at Wharenui stood until 2008. This was a very simple box cottage, with a gable roof and very little in the way of ornamentation. The street-facing elevation was symmetrical, with a door in the centre and windows either side. These were casement windows, which probably replaced sash windows (casement windows did not become common in Christchurch until c. 1910). The house was clad in standard weatherboards, with a corrugated iron roof and it sat on stone piles. The only feature that could in any way be considered decorative was the front door, which was a four-panel door with round-headed glass upper panels, and sat in a recessed niche with angled (rather than horizontal) rusticated weatherboards. The interior of the cottage was not inspected. As such, it is not clear whether the two-roomed cottage referred to in the 1904 newspaper advertisement actually only had two rooms, or whether it had two rooms and a hall (halls were not typically counted as a room). Aerial photographs, however, show that it had just the one fireplace, against the rear wall of the east room, indicating that this was the kitchen.

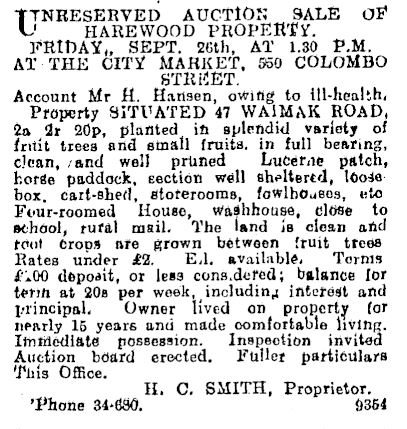

There’s not a great deal of information about Hansen’s life or activities available for the period when he was living at Wharenui. He obtained New Zealand citizenship during this time, sold pick-your-own raspberries, placed advertisements in the paper for work, and variously described himself as a farmer or labourer (DIA 1989, Press 23 12/1901: 8, 2/5/1902: 8). After selling the lease, he appears to have moved around the city, not really settling again until he purchased another 2½ acres at Harewood in 1915 (Sun 16/6/1915: 1). Prior to this, he placed advertisements in the paper looking for work on a fairly regular basis (generally as a ‘rough’ carpenter or unskilled labourer; e.g. Star 27/10/1906: 6, Press 5/11/1913: 14); once he was at Harewood, these advertisements no longer appeared. He sold the Harewood property shortly before he died in 1931, leaving an estate of £260, but with no children (he had – very briefly – married, in 1915 (Sun 15/3/1920: 11, Christchurch High Court, 1931)).

On 9 August 1900, John Larkin was granted Section 38 of the Tamai Hamlet, in Woolston (Lands Department 1901). Like Hansen, Larkin appears to have been unskilled, being described as both a labourer and a dealer (usually a secondhand dealer; Wises 1903: 218, NZER (Lyttelton) 1905-06: 51). In March 1901, the Ranger reported that there was no building on the section, and the situation was the same a year later, when apparently Larkin had not complied with his lease in terms of the value of the house on the section, although he was resident there. By 1903, there were £25 worth of improvements to the property, which was still not enough to comply with the conditions of the lease. Two years later, the value of the improvements had trebled, suggesting that Larkin’s house (which stood until 2014) was built between 1903 and 1905. Larkin was the only person resident on the section. In 1908, Larkin sold the lease (Lands Department 1901).

The house that Larkin built was a four-room house, with no hall. It was a saltbox cottage, clad in plain rimu weatherboards, and sitting on stone piles. The street-facing elevation was symmetrical, and, like Hansen’s house, this is likely to have had sash windows originally. There were no decorative features on the exterior at the time of recording, and it seems unlikely that there were any originally. Inside, the rooms were lined with beaded match-lining (a cheaper alternative to the more common lath and plaster), and there was a back-to-back fireplace between the kitchen and parlour.

Clearly, John Larkin spent considerably more money on his house than Hans Hansen did, and his house appears to have been constructed in anticipation of a family, although I’ve not been able to work out whether or not Larkin ever had one, or even what his age was when he was living there. These houses give an insight into the type of houses that unskilled labourers were building in Christchurch in the early twentieth century. They were little different from the houses that early European settlers in Ōtautahi Christchurch had built some 50 years previously, although possibly better built. They were a type – cottage – that became less and less common as time passed and the villa began to dominate Christchurch’s housing stock, but one that clearly remained an option for those at the lower end of the socio-economic scale to build.

What do these houses and the lives of these men tell me about the working men’s settlements the Liberal government developed in the late nineteenth century? Well, it’s only a sample of two, but neither man stayed particularly long in the settlement in question and both struggled to meet the conditions of their lease. It is notable that both were unskilled labourers, meaning they probably had a particularly precarious existence in terms of both work and income, often not having full-time permanent employment – something Hans Hansen’s story illustrates perfectly. This would have made it more difficult for them to save the money necessary to build a house and comply with the lease conditions. For Hansen in particular, this situation is likely to have been compounded by the lack of public transport options, meaning the area within which he could take on work was limited. Larkin, however, was much closer to the city and to a wider range of potential jobs. Hansen – with his raspberry plot – seems to have put his land to the use the scheme intended, but it is not clear whether or not Larkin did. On balance, while the scheme allowed both men to build a house, neither was able to retain this property, and the scheme probably cannot be regarded as successful for Hansen, who seems to have been of no fixed abode for sometime after this. Somewhat ironically, Hansen would eventually purchase more land and, in fact, fulfil the ideal that the Liberal government had envisaged when they established the hamlet scheme.

Katharine

References

Christchurch High Court, 1931. “Hansen Hans – Christchurch – Labourer”. Accession CH171, R20184940. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

Department of Lands and Survey, 1897. “Lands and Survey Library – Settlement Sales Plans – Wharenui Hamlet”. Accession CH730, R2085471. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

DIA, 1899. “From: Hans Hansen, Riccarton Date: 6 May 1899 Subject: Memorial for naturalisation”. R24925016. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

Ellesmere Guardian. Available from Papers Past.

Ferguson, Gael, 1994. Building the New Zealand Dream. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press with the assistance of the Historical Branch, Dept. of Internal Affairs.

Lands Department, n.d. “Particulars, Terms and Conditions of Disposal and Occupation of Tamai Hamlet”. Accession CH325, R20081115. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

Lands Department, 1898-1929. “Leases in Perpetuity – J. F. Archer Section 13 Wharenui Lands and Deeds reference CL181/82”. Accession CH134, R20017733. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

Lands Department, 1901. “Leases in Perpetuity – J. Larkin Section 38 Tamai Settlement Lands and Deeds reference CL189/115”. Accession 134, R20017921. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

LINZ, 1898. Crown lease 181/82, Canterbury. Landonline.

NZER (New Zealand Electoral Roll). Available from Ancestry.com.

Press. Available from Papers Past.

Schrader, Ben, 2005. We Call It Home: A History of State Housing in New Zealand. Auckland: Reed.

Star. Available from Papers Past.

Sun (Christchurch). Available from Papers Past.

Wises New Zealand Post Office Directory. Available from Ancestry.com.

A note on archaeology and racism

I know that this is primarily a blog for sharing the above and below ground archaeology of Christchurch’s colonial period, but it felt wrong to post something this week without acknowledging and engaging with what has been happening in the world, especially the need to re-examine and actively combat racism and white supremacy in modern society. This is a big topic and one I am skimming the surface of, specifically in relation to historical archaeology and my own personal responsibility to change. Please also go and read the words of black Americans in the United States right now, of Māori and Pasifika here in New Zealand, of indigenous and people of colour everywhere.

(TL;DR – racism is a thing in archaeology, archaeology can be part of the problem, we have a responsibility to make sure it’s not; highly recommend reading all the links at the end).

The image above is a Prattware jar found in Christchurch, made in the 1850s, depicting a scene from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist, anti-slavery book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It is an object that speaks to the history of racism and slavery and oppression in America, and the place of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the abolitionist history of the nineteenth century. It is also, however, an object of British colonialism, one that embodies a tradition of European people co-opting the imagery of black lives, embracing simplistic racialised stereotypes of other cultures, from the concept of a subservient “Tom” or the derogatory performance of blackface to the whole offensive notion of the ‘noble savage’. It is part of a LONG culture-history of systemic racism that has minimalised and dehumanised people of colour, contributing to the unequal and deadly society of today.

The last time I posted a photograph of this artefact, I did so with a caption that acknowledged the relationship of the jar to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but failed to look deeper into the appropriation and legacy of that imagery. Listening and watching and reading over the last week, since the murder of George Floyd, and over the last years, since March 15 2019, since Charlottesville, since Michael Brown and Tamir Rice and countless others (because this has been happening for too long), I’ve thought a lot – as I hope a lot of other Pākehā have – about what I can do, to be part of the solution and not the problem. Mostly, the answer is to support, to amplify and to speak out, to stand up in solidarity and to call out racism when I see it. But, thinking about this jar and my framing of its story, I’m also conscious of storytelling and the power of words, and archaeology, to shape histories and attitudes and unconscious biases, of how much the way we tell our histories maintains that systemic, structural racism.

As an archaeologist, especially an archaeologist whose specialty is the colonial period of New Zealand’s history, one of the things I can do, professionally, is actively decolonise the language I use, be anti-racist in the way I tell the story of the space and time I investigate. I can look deeper, beneath the surface of an object or an event, to always place the work I do on the material culture of European colonial society alongside the violence perpetrated by that society against Māori and against people of colour around the world. I can better acknowledge that archaeology is itself a discipline with roots in the exploitation of indigenous and non-European culture for the sake of European curiosity and profit, something we ignore too often. Historical archaeology in particular is sometimes, I think, so focused on the humanity and story of colonial settlers that we ignore, or downplay, the uglier side of their complicity in a deliberately racist system. We should not.

Archaeologists talk about how “absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence”. It’s a nice catchy phrase that reminds us to think about how the archaeological record – the deposits, the impressions left on the land – was curated by the behaviour of people in the past (it is NOT an excuse for conspiracy theories about archaeological cover-ups, which replace an absence of evidence with speculation that has no grounding in historical reality). Sometimes, the reasons for an absence of archaeological evidence are as telling as the actual evidence might have been and I’ve been thinking about this in historical archaeology, in colonial archaeology, in Christchurch. Māori are essentially invisible in the archaeological record of Ōtautahi Christchurch during the 1850-1900 period. Every single archaeological site in my dataset was occupied by European settlers, every single artefact is European or Pākehā in origin. That invisibility is not benign, not just the way it is, but is instead the result of the deliberate and, in many parts of New Zealand, forcible alienation and removal of Māori from the land and its subsequent archaeological record (it is also a consequence of the European erasure of Māori archaeology from the footprint of Christchurch during the nineteenth century). The predominance of European material culture in post-1850 Christchurch is not something that just can be explained away as a characteristic of that time: it’s a characteristic of that time because it was imposed on the land, a tool of British colonialism in New Zealand. The invisibility of Māori in my dataset doesn’t relieve me of the responsibility to talk about negative effects of colonisation in Christchurch – if anything, it makes it more important that I acknowledge and discuss the systems and structures that led to that invisibility in the first place.

I’m afraid of confrontation. I hate it, I’m terrible at it and it makes me deeply uncomfortable. Writing this post has been a huge source of anxiety and I’m worried about what I’ve said and whether it’s enough or whether it’s too much, but it would be worse to stay silent. People are dying, people are being beaten, people here in New Zealand are suffering as a result of a socio-cultural system that has benefited me, because of my birth and my skin, and allowed me to use my discomfort as a reason not to speak out about the injustice that they are facing, even though I know it’s wrong. It is not okay. The very least that I can do is shoulder that discomfort, knowing that it will never be even a fraction of what is experienced by people of colour all the time, and use what little voice I have to amplify theirs, to actively question and deconstruct the racist systems – the bias, the assumptions, the unconscious conditioning – that I see, in my own work and in the world around me.

Jessie

NB// None of this is anything new, so here are some links, to writing that challenged me and to people who have written about this all better than I ever will:

On the futility of ‘goodness’ in a racist society – https://www.elle.com/culture/career-politics/a32712287/cnn-omar-jimenez-arrest-response/

Everything on e-tangata, but especially this https://e-tangata.co.nz/history/the-land-of-the-wrong-white-crowd-growing-up-and-living-in-the-shadow-of-racism/, this https://e-tangata.co.nz/comment-and-analysis/racism-and-white-defensiveness-in-aotearoa-a-pakeha-perspective/, and these, on police violence against Māori and Pasifika, https://e-tangata.co.nz/comment-and-analysis/we-dont-have-to-go-down-this-path/ and https://e-tangata.co.nz/comment-and-analysis/partnership-is-critical-during-a-crisis/

On institutional racism in New Zealand – https://e-tangata.co.nz/comment-and-analysis/the-racism-that-too-few-of-the-privileged-can-see/, and colonialism and racism – https://e-tangata.co.nz/comment-and-analysis/moana-jackson-understanding-racism-in-this-country/

This, on the recent destruction of Juukan Gorge in Australia https://theconversation.com/destruction-of-juukan-gorge-we-need-to-know-the-history-of-artefacts-but-it-is-more-important-to-keep-them-in-place-139650 and this, on Ihumātao https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/when-worlds-collide-2/

An amazing resource for Māori place names and history in Ōtautahi Christchurch and throughout the South Island – http://www.kahurumanu.co.nz/atlas

Anti-racism resources for white people https://docs.google.com/document/d/1BRlF2_zhNe86SGgHa6-VlBO-QgirITwCTugSfKie5Fs/preview?pru=AAABcoVnEEc*g_KKl6pycPL5FuYxjxWfWQ

On the character and construct of Uncle Tom:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2002/mar/30/race.society

A JSTOR syllabus of articles on institutionalized racism: https://daily.jstor.org/institutionalized-racism-a-syllabus/?fbclid=IwAR0XqLV-pRS9aFSazieLHP2nGmRpFryEszsiYsd58qQeErrL6jriPqOFugI

On race, racism, protest and activism in anthropology and archaeology – https://www.americananthro.org/StayInformed/OAArticleDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=13103

Toward an anti-racist archaeology – https://activisthistory.com/2019/09/27/toward-an-antiracist-archeology/

In New Zealand, more generally, anything by Leonie Hayden, Damon Salesa, Morgan Godfery, Alice Te Punga Somerville, Moana Maniopoto and Moana Jackson, among many others.

Internationally, there are so many books and articles and lists of resources out there on the internet. I’ve personally loved and been challenged by the works of people like Ta Nehisi Coates, Maya Angelou and Maxine Beneba Clarke.

Lost in translation

People say the past is a foreign country (well, L. P. Hartley wrote it in 1953 and we’ve sort of just been repeating it when it suits ever since), which is a sentiment that, as it turns out, is a lot more complicated than I initially thought when I decided it would make a good framing device for this post. I’ve got it stuck in my head now, though, and I can’t think of another way to start this, so I’m just going to run with it. It’s an appealing statement, one that seems to, in six words, encapsulate the gulf that can appear when we look back on past ages and aeons and the people, societies and cultures that inhabited them. However many questions I have about the analogy (and it’s a lot, apparently), I have to admit that it’s also one that seems startlingly apt, sometimes, when I’m researching people and places from long ago. There’s a great deal of familiarity in the past, in the way that people interact with each other, in their motivations and behaviour, in the way they use objects and construct their physical surroundings. But there’s also quite a lot of unfamiliarity, a dissonance between then and now that is apparent in many ways, but perhaps, for me, never quite so much as when I come across terminology and phrasing from the Victorian era that is either completely indecipherable in meaning or somehow close enough to modern English to be even more obviously from a different time (or country).

I’ve already written about language and archaeology on here, in relation to the languages of analysis and recording around the world, and how speaking the same language is not always a guarantee that words have the same meaning. This post takes the same principle, but shifts focus a little to the language of the 19th century, not as a linguist (which I’m not!) but as a researcher who finds that the English of the Victorians sometimes requires a bit of thinking outside the box to translate to the modern day. So, the following is a handful of terms and phrases that a) confused me greatly when I read them and b) turned out to have interesting (if not always good) stories behind their meaning.

“Dead-eye dick literature”

The story behind this phrase involves one of my favourite anecdotes from Victorian Christchurch. I came across it while researching a man named Thomas Pillow, the proprietor of one of the shops I have artefacts from and a man who had the misfortune to be remembered, at least in part, through this misdeeds of his son, Albert. In 1879, at the tender age of 18, Albert decided to a) steal a bunch of antique weaponry from Canterbury Museum and b) hold up a carriage in Riccarton, wearing a black mask with cut-out eyeholes, two pairs of trousers and two coats, armed with a revolver and an antique Japanese dagger, one of the spoils from his trip to the museum.

It did not go to plan.

The people being held up did not take kindly to it, there was a bit of a scuffle and Albert was arrested and charged with assault and, after the police had searched his bedroom at his dad’s house and found the imitation poignard, and two spear heads from the museum, larceny. Headlines at the time had fun telling the story of “Pillow, the Christchurch Highwayman” and the story lived on long enough to be included in George Ranald Macdonald’s Dictionary of Canterbury Biography entry for the Pillow family. In it, Macdonald has this to say about Albert’s actions and motivations: “A youth of 18 after doing a course of Dead-Eye Dick literature stole 2 daggers from the museum and armed himself with a revolver and ammunition. Putting on 2 suits to increase his size, he held up a carriage in Riccarton. He couldn’t quite carry it off and was charged with assault.”

It turns out that “Dead-eye Dick literature” refers to the dime novels of the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century, stories of adventure and daring – often in the American west – that featured characters like “Deadwood Dick”(possibly based on a real cowboy, Nat Love?) and “Dick Deadeye”, among many others. The term ‘dead-eye” seems to be synonymous with marksmanship and straight shooting, although it might also have something to do with sailors but, by the 1930s, “Dead-eye Dick literature” appears to have become a proxy for all dime novels, as this 1937 headline in the New York Times magazine suggests.

The emergence of dime novels seems to be attributed to Irwin P. Beadle and company in 1860s America (well in time for Albert Pillow to have grown up with them) and they were very popular by the 1870s, when they’re first mentioned in New Zealand newspapers. As the decades progress, they quickly become associated with bad behaviour – not just of children! – in newspaper accounts, a kind of anti-moralistic devil-on-the-shoulder kind of influence (not far from the modern day “kids and their videogames!” I reckon). All of which might come to explain why George Macdonald uses the term to explain Albert Pillow’s somewhat ill-fated actions in 1879 (although it’s worth noting that I couldn’t find a reference to dime novels in the 1879 accounts of the incident).

This whole story, and the terminology used in the different accounts of it, is a great example of how much the information in a historical record can be influenced by the time period in which it was written, as well as the person who wrote it. And how much language changes over decades. Macdonald was writing in the mid-twentieth century, about an incident that occurred in 1879, both of which I’m reading about from 2020. It seems likely that the phrase “dead-eye dick literature” would have been as unfamiliar to Albert as it is to me – it doesn’t appear in New Zealand newspapers until the 1900s, despite frequent mention of dime novels themselves in earlier decades, and a lot of the international examples I could find of the term were early to mid-twentieth century in nature, like these “Dead-Eye Western Comics” from 1948. In a way, its use tells me as much about mid-twentieth century New Zealand as it does about Victorian Christchurch, as well as mid-twentieth century attitudes towards objects and events of the nineteenth century.

“Knights of the burnt cork”

In an era that happily named meetings of like-minded people things like the “Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes”, this seems like it could mean anything. But no, it’s a reference to blackface (surprise, racism!).

Blackface is a topic too huge and too complicated to really discuss in a short section of a single blog post (and one that has been written about in detail elsewhere), but suffice to say that minstrelsy, including blackface minstrelsy, was a part of the live entertainment available to New Zealanders during the course of European colonial settlement, from the nineteenth century onwards (unfortunately, it still crops up sometimes, even in 2020). I came across this particular term for it in an account of a ‘juvenile’ minstrel show performed by children at a school in Christchurch in 1879, and it can be found in other advertisements for blackface minstrel shows throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The term itself comes from the use of burnt cork – often mixed with water or petroleum jelly – to darken the skin of the white actors performing in blackface (Mahar 1999). The title of ‘knights of the burnt cork’ serves to imply a gallantry and nobility that is completely at odds with the nature of blackface as a tool that demeans, caricatures and denigrates, but it also – at least to me – evokes the terminology of the Ku Klux Klan, whose members were also called ‘knights’. It seems like peak Victorian whimsy on first reading, but, like so much of that era, the whimsy is just a cover for the deeply terrible attitudes and racism that went hand in hand with European colonialism around the world.