“We shape our buildings; and afterwards our buildings shape us” – so said Winston Churchill. He was referring particularly to the House of Commons’ Chamber, but the statement is true of any building, and it’s a process that works in a myriad of ways. Buildings reflect the world around us, whether by affirming what society values or the norms of the days, or in opposition to that. Those that affirm the values of the day, such as James and Priscilla Chalmers’s house, also serve to reinforce those values and to encourage the behaviours that form part of that, rather than challenging the norm or seeking to change it. And so James and Priscilla’s house reflects the ideal that middle class Victorians aspired to, and is characterised by three things: gendered roles, public and private space and display. You could easily extend that argument to cover much of Victorian life, but let’s stick to houses for now.

Gender, space and display in Victorian houses were all interconnected, most obviously through the connection between public spaces and masculinity and private spaces and femininity. Display weaves its way through those spaces, characterising them as either feminine or masculine and underlying the performance of middle class identity. It might seem strange to us to characterise a space within a house as being feminine or masculine, beyond the obvious example of some children’s bedrooms, although that’s slightly different from the way middle class Victorians thought of space and gender. But interior decoration is frequently characterised as being masculine or feminine – the results of googling “[insert appropriate gender] interior design” are depressingly predictable. And this modern characterisation has at least some of its roots in the Victorian era.

Public versus private space in the home is probably something we’re much more familiar with, and many people are likely to have rooms in their house that they don’t take visitors into, although what rooms in particular probably vary from house to house, depending on the occupants’ preferences. We still use objects in the household along public and private lines, some placed to be seen (recent scrutiny of people’s bookcases on Zoom is an excellent case in point) and others hidden away, or used only to – privately – prepare spaces for public expectations (cleaning products!). There are differences, though – we’re less likely to show off our bedrooms, perhaps. Kitchens, though, are now much more public than they were in the Victorian era, thanks to the rise of open-plan living, changes in gender roles and changes in family life. Ironically, this has led to sculleries becoming a kitchen feature again, as people once again seek to hide the work that goes into preparing a meal, to maintain a sense of order and tidiness throughout. For others, though, the very act of preparing a meal has become an act of performance, particularly with the rise of a ‘foodie’ culture.

And we do still think carefully about how we furnish our rooms and what we display in them, although these features are less likely to be built-in (such as ceiling roses and ceiling cornices) than they might have been in the late 19th century. Recent trends in domestic architectural design, though, turn the fabric of the house into a feature that can be related to identity – the particular types of timber used, for example, can convey a message about what environmental values you hold dear. For many of us, though, living in houses we did not build, a great deal of the personal and social identity expressed within our households comes from the ways we use the spaces we have, and the less-fixed material culture we use to construct, augment and change the material world of the building we live in. In this we are not so dissimilar from James and Priscilla, who – although living in a house they built – would still have used objects and furnishings to reinforce notions of behaviour and space within their household.

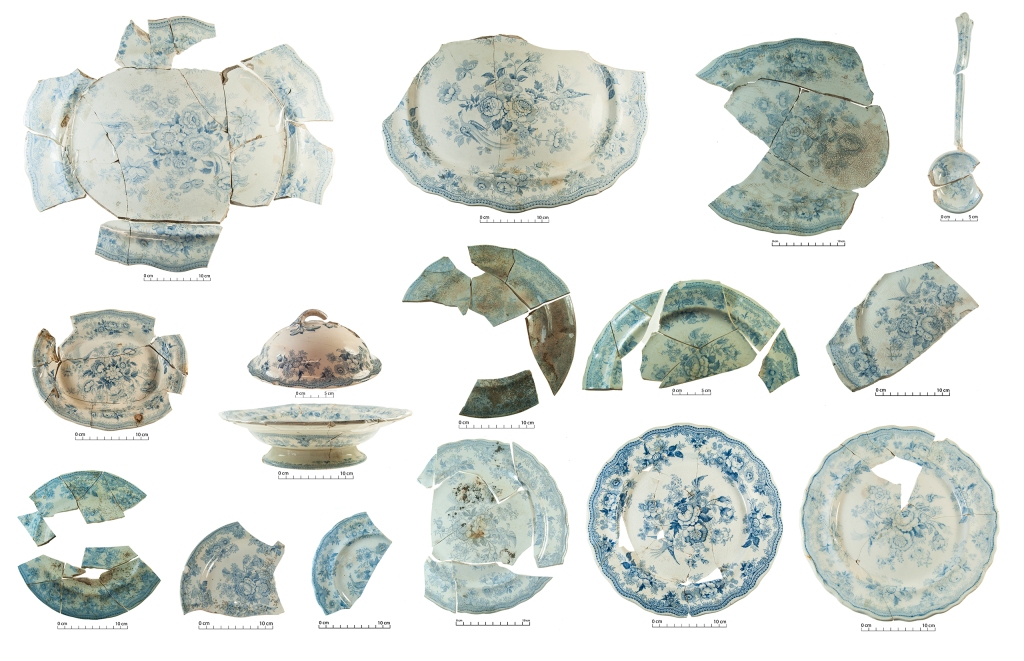

The material culture of a Victorian household can be viewed from many perspectives, on its own or as part of an aggregate that sheds light on broader patterns in a society or culture. Considered alongside the house itself, it’s fascinating to see how it might have been intertwined with the expression of gender, space and display embedded in the physical structure. The designation of certain rooms – like the parlour or dining room – as feminine or masculine is both complemented and contradicted by the use of objects within the room. The more masculine dining room, for example, would have been filled with the material culture of dining, food production and consumption, objects often considered a reflection of women’s consumer choices and women’s labour. Yet, the material culture of the parlour likely complemented its characterisation as a woman’s space, reinforcing a Victorian ideal of women’s roles as hostesses, mothers and industrious members of the household. This may seem a rigid delineation of space to us now, but its legacy is still visible in the gendered spaces of many modern households (“man-caves”, ugh).

Other objects reflect Victorian ideals of gender in a way that is divorced from the spaces they occupy within the house – items like perfume, hair care remedies and clothing connected to broader social concepts of feminine and masculine (as they, irritatingly, still do today), but were anchored to a performance of person rather than household space. In this – as with the use of objects to display wealth, status, class, social identity etc. within the household itself – that performance of identity is not just directed at the observer or, in the case of the household, the visitor, but also served to reflect the household back onto itself, reinforcing how James and Priscilla saw themselves within their world as well as how their world saw them. The things they owned connected them to the much wider world in which they lived – not just late 19th century Christchurch, but the broader expanses of British colonial culture and their own personal experiences, through time and across space. Perhaps not all of it would have been evident on first glance – or ever – to those who entered their home, but their participation in and identification with ideas and groups far beyond the walls of their house would nevertheless have been ever-present within their home, through the structure, through the material culture, and through their own social behaviour.

Jessie & Katharine

References

Beaudry, M., 2015. ‘Households beyond the House: On the Archaeology and Materiality of Historical Households’. In Fogle, K. R., Nyman, J. A. and Beaudry, M. C. (eds), Beyond the Walls: New Perspectives on the Archaeology of Historical Households. University of Florida Press, Florida, pp. 1-22.