Concern about houses in New Zealand – whether the quality, quantity or location thereof – is nothing new. The development of so-called slums, in particular, alarmed nineteenth century migrants to Aotearoa New Zealand, many of whom had come here in the hope of escaping just such problems. By the same token, one of the appeals of nineteenth century Aotearoa to European migrants was the (relatively) unfettered access to land, particularly in urban areas, thanks to the Crown’s cheap acquisition (and in some cases confiscation) of that land from Māori. Not only was land readily available as a result, but there were also few controls on its use (Schrader 2005: 17). The tension here is obvious to us today, but state involvement in the property market (or any other aspect of life for that matter) was considered even less desirable then than it is now (Ferguson 1994: 5, Schrader 2005: 17). The election of the Liberal government in 1890, however, saw attitudes and approaches begin to change (Schrader 2005: 18-19).

Gael Ferguson and Ben Schrader have both documented the solution the Liberals implemented to try and deal with clusters of poor quality housing (Ferguson 1994: 45-45, Schrader 2005: 16-22), which I have summarised below. What I really want to explore, through two case studies, is the houses that were built in these settlements and the people who lived there, in order to move beyond the general to the particular and thus to better understand the individual experience of these hamlets, as they were known.

To solve the problem of slums, the Liberal government decided to establish working class settlements on the outskirts of Aotearoa New Zealand’s cities. These settlements were to be for working men and women, who would be able to lease a section (for 999 years), in return for meeting various requirements, including building a house within a year, fencing the land within two years and establishing a fruit and vegetable garden within three years. Successful applicants had to be able to prove that they had the means to build a house, or that they would be able to do so with a government loan. And they had to be “in all respects a deserving and suitable person” (Lands Department n.d.: 8-9). The sections were to be big enough for a productive garden that would support the occupant in times of little or no work (Schrader 2005: 20). It is perhaps no coincidence that the sections were sometimes referred to as “workmen’s home allotments” (Star 28/10/1896: 3).

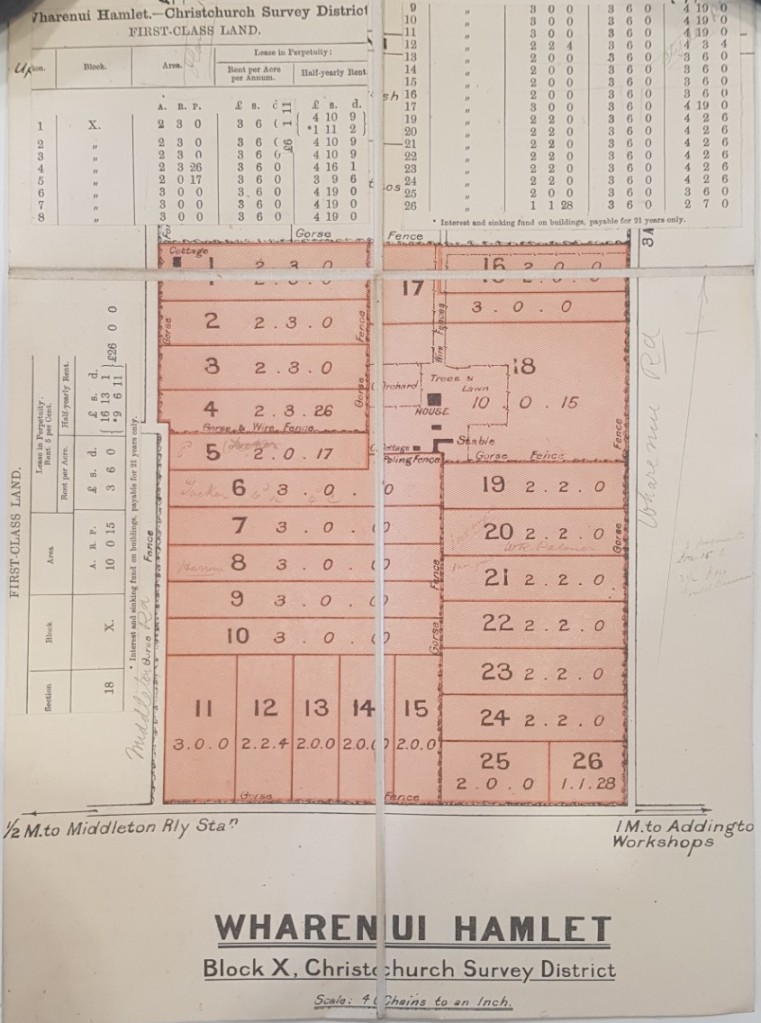

The first of these settlements – or hamlets, as they were to be known – was Wharenui, established in Christchurch (Ellesmere Guardian 3/4/1897: 2). The irony here is that the complaints about slums were generally about Auckland and Dunedin (Schrader 2005: 18) – in fact, I have found little reference to slums or rookeries, as they were often known, in Christchurch in nineteenth century newspapers. The land was opened for selection in March 1897 and, although there were a reasonable number of applicants, several applied for the same sections, with the result that only seven of the 26 sections were taken up (Press 9/3/1897: 1, Star 27/3/1897: 5). Those sections that were not leased to working men were offered on a weekly leasing arrangement to the New Zealand Loan and Mercantile Company and a Mr Chadwick, presumably for grazing (Star 9/4/1897: 2). As would be found throughout the country, the lack of public transport would limit the appeal of this scheme, along with the fact that sections could not be purchased or subdivided (Schrader 2005: 22). People wanted to live near their work, and the other supposed advantages of the scheme were not enough to outweigh the disadvantages.

One of the leaseholders at Wharenui was Hans Hansen, who took up his lease in 1898, not long after he’d arrived in the country from Ribe, Denmark, aged 36 (DIA 1899, LINZ 1898). Hansen leased Section 13, of 2 acres, for £6 12s a year (LINZ 1898). Within a year, Hansen had built a one-room dwelling, fenced the section, sunk an artesian well and was cultivating and gardening. The dwelling, however, did not meet the requirements of his lease, being worth less than £30, and he was granted an extension until 1 November 1901 to build an appropriate house, as well as a loan of £20 to do so (Lands Department 1898-1929). By 1904, when Hansen put the lease up for sale, he had built a two-room cottage on the land to replace the original dwelling (Press 3/2/1904: 10). Early in 1905, the lease was transferred to Alexander Grieve (LINZ 1898).

The second house Hansen built at Wharenui stood until 2008. This was a very simple box cottage, with a gable roof and very little in the way of ornamentation. The street-facing elevation was symmetrical, with a door in the centre and windows either side. These were casement windows, which probably replaced sash windows (casement windows did not become common in Christchurch until c. 1910). The house was clad in standard weatherboards, with a corrugated iron roof and it sat on stone piles. The only feature that could in any way be considered decorative was the front door, which was a four-panel door with round-headed glass upper panels, and sat in a recessed niche with angled (rather than horizontal) rusticated weatherboards. The interior of the cottage was not inspected. As such, it is not clear whether the two-roomed cottage referred to in the 1904 newspaper advertisement actually only had two rooms, or whether it had two rooms and a hall (halls were not typically counted as a room). Aerial photographs, however, show that it had just the one fireplace, against the rear wall of the east room, indicating that this was the kitchen.

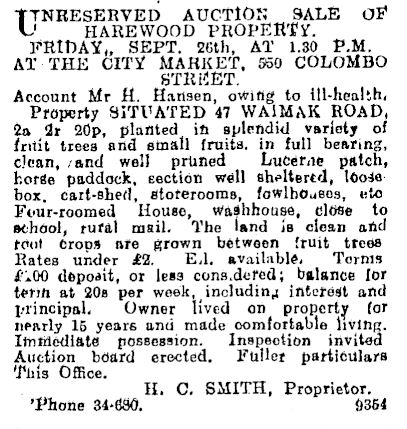

There’s not a great deal of information about Hansen’s life or activities available for the period when he was living at Wharenui. He obtained New Zealand citizenship during this time, sold pick-your-own raspberries, placed advertisements in the paper for work, and variously described himself as a farmer or labourer (DIA 1989, Press 23 12/1901: 8, 2/5/1902: 8). After selling the lease, he appears to have moved around the city, not really settling again until he purchased another 2½ acres at Harewood in 1915 (Sun 16/6/1915: 1). Prior to this, he placed advertisements in the paper looking for work on a fairly regular basis (generally as a ‘rough’ carpenter or unskilled labourer; e.g. Star 27/10/1906: 6, Press 5/11/1913: 14); once he was at Harewood, these advertisements no longer appeared. He sold the Harewood property shortly before he died in 1931, leaving an estate of £260, but with no children (he had – very briefly – married, in 1915 (Sun 15/3/1920: 11, Christchurch High Court, 1931)).

On 9 August 1900, John Larkin was granted Section 38 of the Tamai Hamlet, in Woolston (Lands Department 1901). Like Hansen, Larkin appears to have been unskilled, being described as both a labourer and a dealer (usually a secondhand dealer; Wises 1903: 218, NZER (Lyttelton) 1905-06: 51). In March 1901, the Ranger reported that there was no building on the section, and the situation was the same a year later, when apparently Larkin had not complied with his lease in terms of the value of the house on the section, although he was resident there. By 1903, there were £25 worth of improvements to the property, which was still not enough to comply with the conditions of the lease. Two years later, the value of the improvements had trebled, suggesting that Larkin’s house (which stood until 2014) was built between 1903 and 1905. Larkin was the only person resident on the section. In 1908, Larkin sold the lease (Lands Department 1901).

The house that Larkin built was a four-room house, with no hall. It was a saltbox cottage, clad in plain rimu weatherboards, and sitting on stone piles. The street-facing elevation was symmetrical, and, like Hansen’s house, this is likely to have had sash windows originally. There were no decorative features on the exterior at the time of recording, and it seems unlikely that there were any originally. Inside, the rooms were lined with beaded match-lining (a cheaper alternative to the more common lath and plaster), and there was a back-to-back fireplace between the kitchen and parlour.

Clearly, John Larkin spent considerably more money on his house than Hans Hansen did, and his house appears to have been constructed in anticipation of a family, although I’ve not been able to work out whether or not Larkin ever had one, or even what his age was when he was living there. These houses give an insight into the type of houses that unskilled labourers were building in Christchurch in the early twentieth century. They were little different from the houses that early European settlers in Ōtautahi Christchurch had built some 50 years previously, although possibly better built. They were a type – cottage – that became less and less common as time passed and the villa began to dominate Christchurch’s housing stock, but one that clearly remained an option for those at the lower end of the socio-economic scale to build.

What do these houses and the lives of these men tell me about the working men’s settlements the Liberal government developed in the late nineteenth century? Well, it’s only a sample of two, but neither man stayed particularly long in the settlement in question and both struggled to meet the conditions of their lease. It is notable that both were unskilled labourers, meaning they probably had a particularly precarious existence in terms of both work and income, often not having full-time permanent employment – something Hans Hansen’s story illustrates perfectly. This would have made it more difficult for them to save the money necessary to build a house and comply with the lease conditions. For Hansen in particular, this situation is likely to have been compounded by the lack of public transport options, meaning the area within which he could take on work was limited. Larkin, however, was much closer to the city and to a wider range of potential jobs. Hansen – with his raspberry plot – seems to have put his land to the use the scheme intended, but it is not clear whether or not Larkin did. On balance, while the scheme allowed both men to build a house, neither was able to retain this property, and the scheme probably cannot be regarded as successful for Hansen, who seems to have been of no fixed abode for sometime after this. Somewhat ironically, Hansen would eventually purchase more land and, in fact, fulfil the ideal that the Liberal government had envisaged when they established the hamlet scheme.

Katharine

References

Christchurch High Court, 1931. “Hansen Hans – Christchurch – Labourer”. Accession CH171, R20184940. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

Department of Lands and Survey, 1897. “Lands and Survey Library – Settlement Sales Plans – Wharenui Hamlet”. Accession CH730, R2085471. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

DIA, 1899. “From: Hans Hansen, Riccarton Date: 6 May 1899 Subject: Memorial for naturalisation”. R24925016. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

Ellesmere Guardian. Available from Papers Past.

Ferguson, Gael, 1994. Building the New Zealand Dream. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press with the assistance of the Historical Branch, Dept. of Internal Affairs.

Lands Department, n.d. “Particulars, Terms and Conditions of Disposal and Occupation of Tamai Hamlet”. Accession CH325, R20081115. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

Lands Department, 1898-1929. “Leases in Perpetuity – J. F. Archer Section 13 Wharenui Lands and Deeds reference CL181/82”. Accession CH134, R20017733. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

Lands Department, 1901. “Leases in Perpetuity – J. Larkin Section 38 Tamai Settlement Lands and Deeds reference CL189/115”. Accession 134, R20017921. Archives New Zealand, Christchurch office.

LINZ, 1898. Crown lease 181/82, Canterbury. Landonline.

NZER (New Zealand Electoral Roll). Available from Ancestry.com.

Press. Available from Papers Past.

Schrader, Ben, 2005. We Call It Home: A History of State Housing in New Zealand. Auckland: Reed.

Star. Available from Papers Past.

Sun (Christchurch). Available from Papers Past.

Wises New Zealand Post Office Directory. Available from Ancestry.com.

A great read. My great grandparents lived in Wharenui. My great grandmother’s elder brother was one of the lucky ones getting land. After his premature death it passed to her and after her marriage she and my great grandfather raised their family there. My mother has many memories and their cottage/house is still there albeit much “renovated” and dwarfed by newbuilds. I would love to see the actual plan and be able to workout where along the street other family acquaintances lived – and where my great great grandparents were living too. A holiday in Christchurch is required I think.

LikeLike