This isn’t the post I’d originally intended to write this week, but who of us right now is doing what we thought we’d be doing even at the start of this week, let alone a few weeks ago? As the week has progressed, it has become increasingly difficult to see the relevance of that original idea in the current time and place. So, inspired by the work of a colleague (whose excellent blog post you can see here), I started thinking more about isolation in 19th century Aotearoa New Zealand. What follows is a very once-over-lightly and rambling consideration about the different types of isolation experienced by the 19th century settlers of Canterbury, thinking about the sites of isolation I have worked on or know about. I’ve not discussed the types of isolation that Māori experienced during the century (although some may well have been the same as the European settlers, but there would also have been many types of isolation caused by colonialism), as I am in no position to do justice to this (but see this).

Isolation actually forms a fairly prominent theme in Aotearoa New Zealand’s historiography, thanks largely to the work of Miles Fairburn (1989). I’ll confess that I’ve not read all of Fairburn, but I think I’ve read enough, and enough about his work, to be able to summarise his arguments reasonably accurately (bearing in mind that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing). I should say, too, that I’m going to focus on what Fairburn had to say about isolation in 19th century Aotearoa New Zealand, not his overall thesis. Fairburn (1989: 173) calculated that, prior to 1991, some 36-47% of the population did not have any physically close neighbours (I would contend that the methods used to generate this figure were not quite as robust as might be desirable – to be fair, it is not easy data to generate). He argued that this physical isolation was compounded by being a significant distance from ‘home’ in a strange country, without family and friends. He went on to argue that this isolation, in conjunction with relatively high levels of land ownership and relatively high levels of what he called transience (basically that people didn’t live in any one place for particularly long), combined to create an atomised society. This society was characterised by weak social bonds and high levels of drunkenness and violence (Belich 1991: 673). Subsequent work has found a more nuanced picture, and his work has been critiqued for not recognising that important social bonds formed in the face of this physical isolation (Ballantyne 2011: 61-62, Belich 1991: 674).

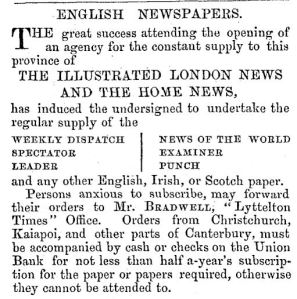

But it remains true that many of Aotearoa New Zealand’s 19th century settlers had left their homes to move to the other end of the world, and many came knowing that they were unlikely to see their family and friends again – I still cannot imagine the leap of faith that requires. Of course, in some cases, family and friends came too: the family of Ernest Oppenheim, who built one of the houses I’m researching, arrived in Christchurch gradually over a ten year period, most of them as adults (DLS 1865, 1872. And while others arrived on their own, they might have been attached to a broader community through religion or country of origin (Fraser 1997). While it was a lengthy boat journey back home, it was by no means impossible: Jessie’s work has found evidence of business owners travelling back to England for business purposes and I have come across families that travelled back simply for a visit. To be fair, this was often a visit of several years and probably the preserve of the wealthy. While it’s not the same, letters appear to have flown back and forth across the oceans, between New Zealand and family members who had not emigrated (Porter and Macdonald 1996: 2). Similarly, this was the age of the telegram, and English newspapers in particular were readily available in New Zealand’s cities, albeit somewhat out of date. All of these would have provided valuable and important connections between those who emigrated and those who did not.

For some settlers, there was also a very real isolation from others, even in this country. Take Mrs McRae, for example, who lived on Stronechrubie station*, way up in the headwaters of the Rangitata River, from about 1878-1892 and apparently went some 10 years without seeing another woman (Acland 1975: 301-302, 304; Brown 1940: 218). Pastoral stations in general lent themselves to isolated communities at least, if not always isolated individuals. The early boundary keepers of Canterbury (who were, as best my research has identified, fairly few and far between), however, would have been much more isolated, as would the occasional shepherds who lived out on the far reaches of the shepherd. These men would have lived on their own year-round, with just occasional visits from other station workers (I honestly don’t know whether wives might have lived with them).

While this isolation must have been pretty hard to deal with for some, there were others who actively sought it out. Take for example, Wyndham Barker, who I’ve written about before over here (and here), established an ice rink on the north bank of the Rangitata River in the 1930s, in the lee of Mt Harper. He and his wife, Brenda, lived here year-round – even today, it’s an hour (including a jet boat ride) from the nearest town (Geraldine). And that’s the quickest way to get there. While things would have been busy there in the winter, the Barkers would have lived in splendid isolation in the summer – and the spectacular scenery would have made it quite, quite splendid.

For those living in the cities, there was much less obvious isolation, although one of the criticisms levelled at city dwelling is the isolation that can be experienced in spite of being surrounded by so many people. It is difficult to explore this type of isolation archaeologically, however. Perhaps one of the more obvious ways that people would have experienced isolation in Christchurch is through physical and forcible isolation, in either gaol or the asylum. As with the other sites of isolation discussed here, these were sites of both physical and social isolation, but the social isolation in these cases was much more deliberate. The residents of these institutions were being isolated from the rest of society for what was believed to be the benefit of both society and the individual who was being isolated. Reality, of course, may have been very different for all concerned.

What I kept thinking about, though, as I wrote this post was that while all these people were isolated, and some in very remote locations, they all remained connected to the world in different ways. At the Sunnyside Lunatic Asylum, in the early years at least, the public were encouraged to attend a range of events at the asylum, including dances, plays, church services and cricket matches (Seager 1987). Station diaries reveal a considerable amount of to-ing and fro-ing between different stations, whether for business or pleasure – there was the seasonal round of the shearing gangs, station employees would often go and carry out work on adjoining properties, and then there were social events, too, in the form of balls and other parties (Barker 1883: 90-91, 98). And I’ve already mentioned the various ways 19th century settlers remained connected to the world they’d left behind. From this I drew two conclusions. One: while life in 19th century New Zealand might seem isolated at first glance, once you start to look into it, it wasn’t. You might not have been able to video chat with your friends from all around the globe over lunch, but expectations were different then. And this connects to my second moral: our connections to people matter. This is stating the obvious, particularly in the current circumstances. But it’s worth remembering here and now that these connections have always mattered, and that our forebears coped with this isolation and that we will too. Humans are resilient and social beings and we will always find ways to connect with others in our isolation.

Katharine Watson

*A station (also known as a run) was a large landholding, typically of tens of thousands of acres.